Spotting rare, native ladybugs

At our Pine Bend Bluffs restoration this summer, we found the glacial lady beetle, one of over 50 native (now uncommon) ladybugs in Minnesota. (Photo by Chris Smith)

Lady beetles (also called ladybugs) are one of the most common insects we encounter in the summer. They may be the first insects toddlers can identify, easily recognizable because of their bright red color and contrasting black spots.

What you may not realize is that virtually all of the lady beetles you're likely to see in Minnesota are not native, but one of three species that were brought to the U.S. from Europe and Asia: the multi-colored Asian lady beetle (Harmonia axyridis), the seven-spotted lady beetle (Coccinella septempunctata), and the variegated lady beetle (Hippodamia variegata).

The multi-colored Asian lady beetle

The multicolored Asian lady beetle arrived relatively recently to Minnesota in 1994, but is now the most abundant of any lady beetle species. It was originally brought to California over a hundred years ago to control pecan aphids.

This is the lady beetle that enters our homes in the fall, looking for shelter. They sometimes bite and release a foul odor when handled. (For more information, see the U of M Extension guide.)

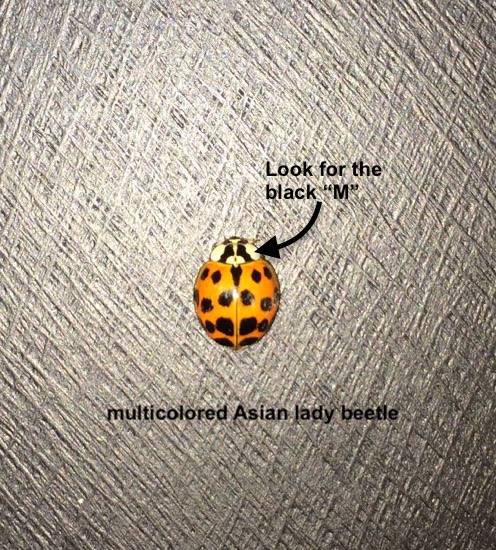

Look for the black "M" behind the head to identify a multicolored Asian lady beetle. (Photo by Karen Schik)

True to its name, this species can be highly variable in colors and patterns. The most common appearance is red with 19 black spots, but it can have no spots at all or somewhere in between. It can be gold or orange. The most reliable identifying characteristic is the black 'M'-shaped marking behind the head.

The seven-spotted lady beetle

The seven-spotted lady beetle may be the "classic" image many of us have of a lady beetle — red with three spots on each wing and one in the center. It is the most common lady beetle in Europe and became established in the U.S. in the 1970’s, soon spreading throughout North America.

How hard is it to spot a native ladybug?

Like the native lady beetles, the non-native species are voracious consumers of aphids, so that's a positive thing for our gardens and crops.

However, the non-native species have largely replaced the native species. No one really knows the full implications of that. At the very least, ecosystem stability is strongly correlated with diversity, so a dramatic decrease in the numbers of species in Minnesota is not a positive thing.

Three species in particular used to be quite common and are now very rare: the two-spot, the nine-spot, and the transverse (Adalia bipunctata, Coccinella novemnotata, Coccinella transversoguttata, respectively).

Although many lady beetle species have some variation of red with black spots, there are over 50 native species in Minnesota, and their coloring ranges from yellowish to brown to black, with or without spots and some with stripes. You can see a poster of them at the Field Ecology website.

Recording the lost ladybugs

Is there anything we should do to help? If you have a smartphone, you can look for lady beetles and help record them.

The Lost Ladybug Project has an app that you can download to your phone. When you see a ladybug, upload a photo using the app even if you can't ID it, though they offer resources to help you if you're interested. (You can also check out this online bug ID guide.)

Gathering this information can help researchers better understand the population status and impacts of lost species.

If you're an FMR supporter, you're already helping! We look for ladybugs and more in our restoration wildlife surveys. In 2019 at the FMR savanna restoration at Flint Hills Resources — our longest-running project — we found the native glacial lady beetle Hippodamia glacialis. Get involved in our restoration work by signing up for a volunteer event.