Winter dormancy: its more work than it sounds like

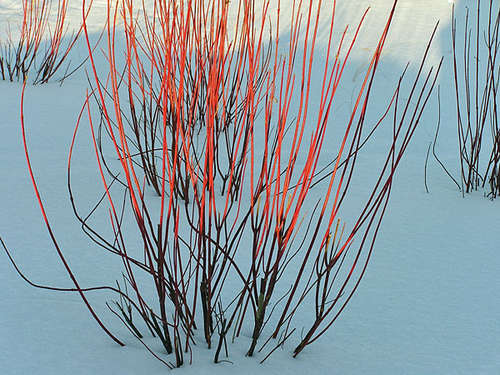

Red-stemmed dogwood buds are protected against extreme temperatures (-100 F or more), but once they break bud, they can be killed by the slightest frost!

Photo: Minnesota Public Radio

Like it or not, winter is upon us. How do plants prepare for the long, cold winter months? For plants, winter is akin to a cold desert, with no or little available moisture and freezing temperatures that leads to damaging ice crystals to form in their tissues. However, different types of plants have evolved to have different coping mechanisms:

- Herbaceous annual plants die every year and rely on seeds to continue their populations.

- Herbaceous perennials partially rely on a strategy that utilizes the protective properties of the ground itself: their aboveground parts die back each year, leaving the roots to regenerate next years top-growth.

- Biennials form taproots and rosettes of basal leaves during their first year, which stay low to the ground and are generally not harmed by the cold.

- In woodlands and forests, woody plants gain some protection by grouping together, ameliorating the effects of wind and temperature. By virtue of their tall, aboveground parts, though, woody plants must survive a wider range of cold temperatures. The rest of this article will explore their survival strategies.

Whats going on inside woody plants, trees and shrubs as winter approaches? Dormancy which is more than a simple or seasonal pause, but a series of physical and physiological changes. This process starts gradually, beginning in late summer and speeding up during autumn. Plants send energy downward to the roots, and the fluid in their cells becomes super-cooled or saturated with solutes, similar to antifreeze. Scales form over buds to protect them from desiccating or drying out, and from freezing temperatures. Interestingly, woody plants roots do not enter full dormancy, but become quiescent adverse environmental conditions trigger a sort of resting state, which can then be broken once conditions improve. This makes sense, since roots are respiring organs they need to breathe.

When it comes to dormancy, timing is everything. If a plant enters dormancy too soon, it loses the opportunity to photosynthesize, grow and store more energy before settling in for the season, and it could eventually be out-competed by better-adapted plants. However, if it waits too long, it risks frost damage and desiccation. Temperate-zone plants take their dormancy cues from the sun or lack thereof. As days shorten and nights grow longer, plants physiologically react. This "photoperiodism" is instrumental in the dormancy process. And its not so much the shortening of daylight, but the lengthening of nighttime thats critical. Its all quite mechanistic. Phytochrome, which absorbs red light and far-red light (light at the extreme end of the far-red spectrum), works in combination with a plants innate circadian rhythms, to initiate both dormancy and flowering. A form of phytochrome builds up, in the plants tissues, in the dark, which triggers the production of proteins and hormones. Eventually, plants enter a state of rest, and will not grow even though all other conditions are favorable. Duration of their resting period varies by species, but is controlled by threshold low temperatures. To overcome rest, woody plant buds must be subjected for four to eight weeks to low temperatures, 24-50 degrees Fahrenheit. This rest period ensures that they do not leave dormancy too soon, which could be disastrous for them. Interestingly, extremely low temperatures have little or no more effect than the threshold temperature for overcoming dormancy. Some species, like red-stemmed dogwood, have buds that are protected against extreme temperatures (-100 F or more), but once they break bud, they can be killed by the slightest frost!

For more information

- University of Minnesota, "What are you woody plants doing right now?"

- University of MN Extension, "How plants stay warm in winter"

- The University of Minnesotas Sustainable Urban Landscape Information Series

- Centre for Plant Biotechnology and Genomics

- Kimballs Biology Pages